Writing vs. Desire

"...a fire in my bones..."

I’ve been writing on Substack now for just over a year. Last October, I committed to writing and publishing something once a week. This wasn’t the first time I had written regularly, even weekly: working as a priest for over 6 years, most weeks I wrote and delivered a sermon weekly; as a graduate student in both seminary and university, I obviously had to write a lot as well.

But part of what I learned from those experiences was that I could and would write regularly—if I had to. Left to my own devices, I would come up with dozens of ideas and even brainstorm them—but never actually sit down and write them out. Some combination of laziness, procrastination, uncertainty, and sheer orneriness prevented me from actually putting pen to paper (so to speak). After all, I’d had a blog on wordpress for about a decade, and only managed to write there every few months (at best!)

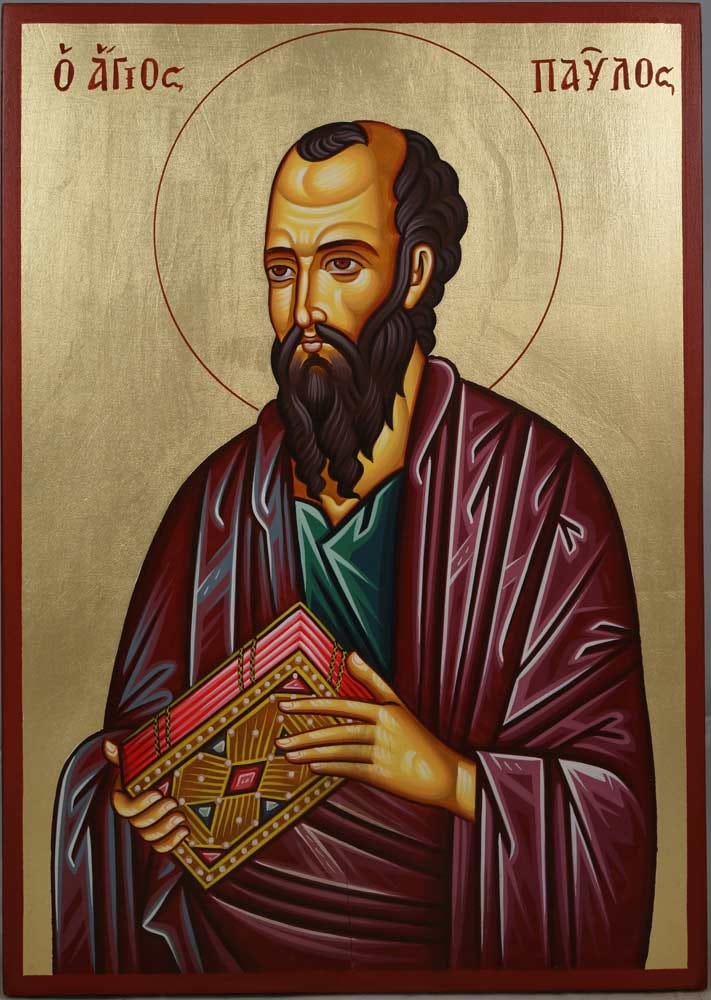

However, when papers were due at school or I knew Sunday sermon was looming, I never had any problem writing. When I knew I had to, I wrote, and got things done on time. So my commitment to writing here weekly was really just a way to compel myself to do what I knew I could do—indeed, what I knew I wanted to do, and yet still simply wouldn’t choose to do. As Paul laments, “I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate.” (Romans 7:15)

So I’m glad that I’ve maintained this discipline—the discipline, that is, of simply choosing to do what I want to do—for the past year. Admittedly, some weeks, I just barely squeaked by, for example: publishing sermons that I had written anyway because I was substitute-priesting at a parish that week. Even so, I never missed a week, and I think the discipline of simply writing has, indeed, been good for me.

What I find most interesting about this situation is that even now, a year into this practice, I still for some reason often dread having to write. Indeed, I didn’t want to sit down and write this! But, once I actually sit down at the keyboard and start, I find the words tend to flow pretty easily and I even enjoy the process. I can often get 2 or even 3 thousand words down in a single session (though I imagine, ever-suffering reader, that you often wished I stopped rather sooner).

But if I basically always enjoy writing—or at least feel fulfilled in doing so—why do I even now continue to dread writing? And this isn’t just an issue for me alone, because I a lot of writers—both professional and amateur—report having this same experience of tension and struggle. Why do we not want to do something that we enjoy and gives us meaning?

This is not a rhetorical question! If you have theories, please leave them in the comments. But what strikes me is the odd juxtaposition here of desire and aversion, of potential and actuality. We often assume that our desires are straightforward: someone likes the taste of cheesecake, so they eat cheesecake. Someone finds a comedian funny, so they watch their standup. Someone thinks someone else is cute, so they kiss them. Desire, we assume, is simple, and its satiation is simple too: grasp and take hold of whatever it is that you desire.

Yet if my experience of dreading writing is any indication, this is not always the case. We can fear what we love. Perhaps this is due to the intertwining of different desires and aversions: I want to have finished writing this piece and have the satisfaction of hitting “publish”, but my laziness means I don’t want to actually have to do the work. Maybe; I’m not so sure. I don’t actually dislike the mechanical process of writing, and it’s hardly difficult physically, so I’m not sure laziness per se is the problem (in this case; undoubtedly laziness interrupts me in many other tasks).

As I said, I don’t know the answer to this question, but it seems an important thing to ponder, since I think if we consider it closely, we will see other questions falling out from this one. Our sense of self, after all, is often little more than a collection of desires: I am the person who wants this and dislikes that. But if our desires and aversions are themselves a bit ephemeral, hard to pin down, and even in conflict with each other, then perhaps our sense of self may not be as secure as we often take it to be. And indeed, all serious spiritual traditions insist, to varying degrees, that this is the case.

And perhaps, of course, the deeper lesson lurking here (though we probably don’t want to notice it!) is that bare, blind desire itself may not actually be the best guide for how to live well as a human. Perhaps instead we need to learn what it is proper and good to desire, and only orient ourselves to that. But such a task, of course, is the work of a lifetime. “If I say, “I will not mention him or speak any more in his name,” then within me there is something like a burning fire shut up in my bones; I am weary with holding it in, and I cannot.” (Jeremiah 20:9)

Very few, it seems to me, desire the labor of writing—no more than one might desire the labor of cleaning or yard work or being at church at 7am Sunday morning. Some are more or less inclined toward one form of labor or another, and most (I hope) find satisfaction in the successful outcome of their labor. Any yet, there is something unique about a writer’s relationship with their labor. Many words have been devoted to pondering the authors’ love-hate relationship with these words. We all assume it comes so much easier to others and are never assuaged to hear that often it doesn’t (David Brooks writes about this often). If AI revealed anything, it is that there is something much more powerful about language than we ever fully understood. I’m less worried about AI than I am of discovering the postmodernists might have been right— that intelligence, meaning and reality are contingent on language (of all of the theories of AI, it is the LLM that has unleashed it). We also know from our theology the connection between words and creation. It’s not a coincidence that we translate logos into “the word.” Our creation story reveals not the materialist instruction manual our empirical minds insist but rather defines creation itself as the act of naming, categorizing, abstracting. Perhaps the labor of writing may be closer than we think to desire…not only because of the pleasure (ecstasy?) derived from insight, but because there’s something about it we fear. If finding the right words is more than quotidian labor but rather the essence of creation itself, we should enter into it with a healthy dose of fear…?