Monotheism vs. Monotheism

Between an inclusive and exclusive conception of God

I recently finished John Peter Kenney’s Mystical Monotheism, a study of the development of monotheistic ideas within Greek pagan philosophy that culminates in Plotinus’s sublime view of the One in Neoplatonism. I heartily recommend the book, which manages to be clear while also densely packed with technical insight.1

There’s a whole lot to like in this book, but one distinction Kenney makes struck me in particular as extremely important: Kenney insists that, in understanding the development of monotheism—at least in the pagan Greek context—we must distinguish between what he variously calls “exclusive” (or quantitative) monotheism versus “inclusive” (or qualitative) monotheism. This is a distinction that definitely makes a difference, so I’d like to unpack it here and offer some reflections on how important this distinction is not only to the history of philosophical theology but also to genuine monotheistic spirituality of any tradition. (I have written before about the difficulties, but also wonders, of trying to talk about God in a philosophically coherent way. I see this post as not only a reflection on Kenney’s work, but as a continuation, or perhaps intensification, of those previous reflections.)

Kenney only mentions these specific terms a few times in Mystical Monotheism2, yet the distinction pervades the whole work and is really the key to unlocking the trajectory of Neopythagorean and Middle Platonist thought as they converge and mature in Plotinus’s Neoplatonism. Kenney points out that Greek philosophy after Plato is focused on questions of unity and simplicity—Plato is concerned with providing a unitary account for reality and our experience of it, and his form-realist metaphysics is meant to provide the framework to do so. Yet, somewhat confusingly (at least to later Christian, Jewish, and Muslim philosophers), even as the philosophical descendants of Plato embrace an increasingly unified view of reality, their religious life remained bound to the polytheism of the traditional Hellenic pantheon. Indeed, as the centuries between Plato’s life and the turn of the millennium unfolded, most Greek-speaking people recognized more, not fewer, divinities worthy of worship (Egyptian and Persian deities, in particular, became quite popular in Greece and Rome).3

In other words: even as historians of philosophy note an increased interest in a basically monotheistic-sympathetic view of reality (all things unified and coming from one, or at most two, sources), religious practice was actually diversifying and seemed just as committed to polytheism as ever before. How do we explain this apparent divergence? Aren’t these two intellectual and cultural developments mutually exclusive?

Here is where Kenney’s distinction about types of monotheism is crucial. While those of us raised in the Abrahamic traditions are most familiar with what he calls exclusive or quantitative monotheism, Greek thought was developing what he calls inclusive or qualitative monotheism. Because we so often understand monotheism through the first lens, we are ill-equipped to see it through this second one. And, as we will see, that’s not only a problem for understanding the history of philosophy, it’s a problem for monotheism itself.

Exclusive or quantitative monotheism is relatively straightforward: on this view, one might believe in a multitude of gods (Zeus, Apollo, Aphrodite, Osiris, Mithra, Indra, Agni, Vishnu, etc.). That is to say, one sees reality as a place within which there is a class of beings which have divinity as one of their properties. Then, over time, perhaps due to philosophical reflection (or the act of divine revelation), one might decide that, in fact, of all of these various gods, only one is actually existent, only one is truly real. After this change, one still sees reality as a place where there is a class of beings which has divinity as one of its properties, but it just so happens that that class only has one member. Perhaps we will assign a particular name to this divinity (such as Aten4 or Yhwh) or perhaps we will simply refer to this deity more generically as “the god”5, or even just as God, with a capital “G”.

So this is exclusive monotheism, because it is a monotheism that essentially “begins” as polytheism, and then excludes all deities except one. And it is quantitative monotheism because this approach to monotheism focuses on the numerical uniqueness of the one divinity; though divinity may be a class, this particular, singular divinity is the only member of that class.

This approach to monotheism is, as I said, straightforward. It makes a lot of intuitive sense, and is almost certainly how most people will understand monotheism at at least one stage of their spiritual and intellectual development. Yet Kenney insists that Greek monotheism took a different path: inclusive or qualitative monotheism.

This second approach, like exclusive/quantitative monotheism, also begins with polytheism. However, instead of focusing on the number and nature of the divinities, it is instead focused on reality as such. Remember that, for exclusive or quantitative monotheism, divinity is taken for granted as a class of beings within reality. The nature of reality itself isn’t questioned or interrogated. It is taken for granted as a sort of “background” state of affairs.

But serious philosophy takes nothing for granted—or, at least, it tries not to. Philosophy wants to question everything, and seeks always to answer every “why” question that can be formulated (this does not mean it always succeeds in providing an answer!) For Socrates, Plato, and those that came after them, the fundamental question was how to explain the seeming unity of things—that all things interact in some kind of harmonious, rule-based manner, despite all their apparent differences.6 Plato’s theory of universal forms—intelligible “beings” that grounds particular experiences while not being any particular thing themselves—was meant to provide a framework to help explain this unity. Yet, on its own, the system of forms was not enough. The basic question of why anything exists at all—including the forms themselves—remained unanswered.7

We see this effort to provide a grander unifying principle of things evident even in Plato’s own works, and this emphasis on uncovering the fundamental unity of things only accelerated among many of his later disciples.8 It certainly seemed that reality must be unified at one level of analysis, since every diverse thing is able to interact with other diverse things, and they seem to occupy one shared reality, with one set of rules (or at least one overarching set of sets of rules) governing both their particular being and their interactive behavior, and all of this points to a primordial unity between and within all things.

Yet, how can this speculation about unity be reconciled with the actual diversity of things as we experience them? Even if the interaction of diverse things points to some real unity, the unity itself seems absent, and, indeed, unimaginable—any thing I can imagine has its identity precisely in explaining how it is not something else. So, much of Middle Platonism focused on trying to explain how a primordial oneness somehow erupted into multiplicity. By and large, such efforts were not successful, and indeed much of Middle Platonism is dominated not by systems that point to a fundamental unity, but rather systems that couldn’t get beyond a fundamental metaphysical dualism—there was some kind of source of form, being, and order, but this source interacted with the distinct and separate reality of matter, which was chaotic and diverse. Middle Platonism, then, though driven by a desire to disclose oneness, found itself largely incapable of truly conceiving it.

However, Kenney argues that, drawing on the fundamental insights of Parmenides and a few other Platonic dialogues, an answer to this fundamental contradiction in Platonic thought began to form: whatever the unity of reality is, it cannot be some kind of being, not even the first or “supreme” being, because every being is itself already both particular—that is, one thing among many, already marked by plurality, its identity known only in its being contrasted with something it is not—and also defined by something other than itself—that is, contingent, metaphysically dependent on something more metaphysically primal. But the genuine unity must be neither of these things: it must be truly One and also completely necessary and absolute.

The crucial insight came, according to Kenney, with the Neopythagorean philosopher Numenius. Numenius recognized the conceptual aporia of the philosophical search for oneness: philosophers were seeking unity, but seemed to think that unity itself could be an entity within the realm of multiplicity (that is, our world, whether considered conceptual or physical). Even as philosophers recognized that, of course, unity could not be an entity within multiplicity, one thing among many, they seemed unable to develop a method that could liberate them from this method, and so they remained confused. Numenius essentially flipped the question on its head: if unity grounds all things, if it is the condition-of-possibility for multiplicity but cannot be contained as an item with the realm of multiplicity, then of course unity must just be, well, the unity of the multiplicity. In other words, unity is not an item within the world because the world is itself contained within unity.

Instead of searching for unity as a concept that could be related to other concepts, Numenius realized that unity was rather the condition-of-possibility of all concepts, rather that one among them. Unity was not some entity that existed before all other things in some chain of temporal causation; rather, unity was the very metaphysical ground for temporality in the first place. Searching for unity among the concepts, among the forms, was like searching for a grocery story inside a box of cereal which is itself inside that grocery store, only infinitely more erroneous. It was a massive category error, thinking of unity as a thing rather than as the source of things as such.

Even so, Numenius did not develop a truly comprehensive philosophy that really answered all the critical questions raised by the Greek philosophical search for unity. But he had made it clear what kinds of traditional methods of trying to answer those questions would not work, and he had also arrived at a metaphysical theory that would prove extremely important in later monotheistic thought: the degrees of divinity.

Numenius argued that if all things, even in their multiplicity, participate in unity—being both governed by that unity in their interactions and also metaphysically contingent upon that unity as the absolute condition-of-possibility for existence as such—then that means that all things share in unity, all things already are unified, even if that truth is only partially realized in their current state as one-thing-among-many, or if that unity is simply not recognizable by an observer caught within multiplicity. And here Numenius drew on a crucial insight that had long been lingering in Neopythagorean and Middle Platonist thought. Though most (perhaps all?) Neopythagoreans and Middle Platonists seemed to have respected the validity of Greek polytheism, they had long recognized that, when speaking of divinity, there was the divine, and then there was The Divine. Hermes and Aphrodite might have been very powerful, immortal (or at least nearly so) beings, but they were still beings among beings, defined by something more fundamental than themselves and having to play by the rules of reality (even if their ruleset was broader than the one we humans had to play by).

In other words, beginning at least with Socrates himself, there was a recognition that the gods were not the highest power in or of reality, they were part of reality, not reality itself, much less the “cause” of reality. But the unity that philosophers had been searching for did seem to refer to this deeper, more fundamental, final, absolute truth of reality. By identifying the absolute, uncaused, defining unity of things with divinity, Greek philosophy was moving towards its own understanding of monotheism.

But, as already indicated, this monotheism is different in important ways from the commonsense understanding of monotheism presented above as exclusive or quantitative monotheism. We can see this in the history of its development, summarily sketched above. While the exclusive/quantitative monotheist sees their deity as the only member of the class of beings which are divine, as a thing within reality that happens to be singular, Numenius stressed that the truly divine, the unity of all things, was not a member of any class of anything, but rather the very foundation for reality itself: the formless cause of forms, the source of being beyond being, the non-category which itself contained all categories.

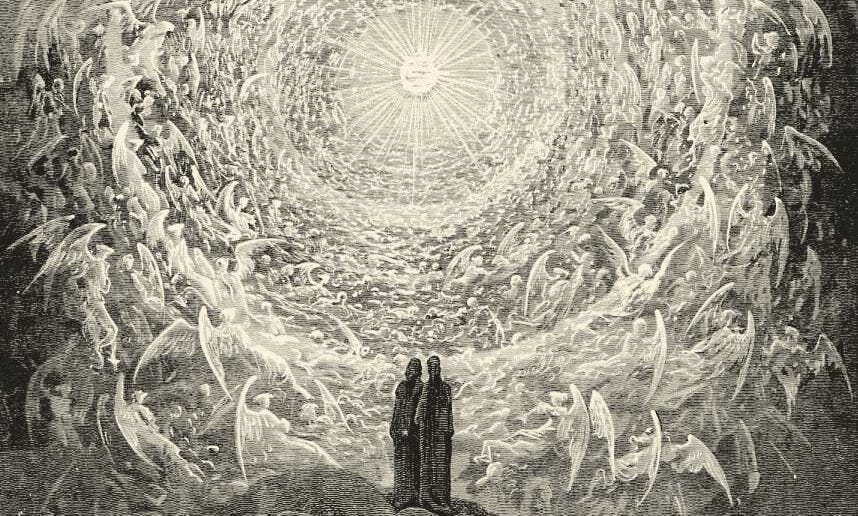

This insight generated a wondrous paradox: on the one hand, this God cannot be in the world as one being among many—God must be truly transcendent. Yet, since this unity-of-all-things is also the very cause and sustainer of all reality, to the extent that anything exists at all, it must exist by the immediate causal power of God. In that sense, God is infinitely intimate to reality, to every particular being—God is utterly immanent, because God is the ground for the reality of every existent, full stop. To return to my (admittedly clunky!) grocery metaphor: although I can’t find the grocery store inside a box of cereal which is itself sitting in the grocery store, even so, and at the same time, when I begin to search for the grocery store in the cereal box, I have already found it (though I don’t realize that at the time), since I am standing in the grocery store the whole time. Now, of course, I don’t possess or contain the entirety of the store, but I do participate in it nonetheless. The store (in this example, quite literally) contains me, and so I participate in it, even if I don’t realize that.

Likewise, Numenius insisted that everything that exists participates in God, simply by virtue of existing at all. Thus, his doctrine of the degrees of divinity: in one sense, everything is divine, simply because everything is continually caused by God. Of course, not everything is equally divine as God is—and everything but God gets its divinity dependently, from God—but even so, nothing can be said to be wholly devoid of divinity either (this emphasis on (a fully transcendent) God as being perfectly and fully divine, while all created things are divine only by participation, is one of the ways this perspective is clearly demarcated from any kind of mere pantheism.). This is why Kenney refers to this view as “inclusive” or “qualitative” monotheism: because this view of the one God includes everything within it, nothing is being fully excluded from divinity. Likewise, one could understand Numenius as arguing that divinity is a quality—the quality of being caused and sustained by God, and thus a quality that all things have, to some degree: thus, reality is a series of degrees of divinity.

It’s crucial to note how different this view of things is from the exclusive or quantitative view, which sees God as a specific, numerically singular entity that exclusively has the quality of divinity itself. As I hope my brief summary of Neopythagorean and Middle Platonist philosophy above shows, such a monotheism ultimately results in a deity who cannot do the work that monotheism needs divinity to do. If the deity is some entity within reality, some existent being, then the deity is caught up in multiplicity, one being among other beings, one-thing-among-many. Such an entity is contained within reality, and so can’t possibly explain why reality happens. Likewise, such an entity would be defined by the rules of being, rather than being that which defines all things. Finally, such a being would be metaphysically contingent upon some more fundamental reality, rather than being the primal cause, the ground, the condition-of-possibility of all things.9

In short, the deity of exclusive/quantitative monotheism cannot be the God who is the source of all things, the absolute ground of all being and becoming. Indeed, someone has suggested that this form of monotheism could be confusingly, though accurately, referred to as “mono-poly-theism”, since it does not really see any difference in kind between its deity and, say, Zeus or Mithra. Exclusive/quantitative monotheism sees the deity as the sole genuine example of the human religious concept of divinity. But Socrates, Numenius, and, later, Plotinus, will see that for God to be real, God must be much more than this.

What is perhaps most ironic about the development of this much more robust inclusive, qualitative monotheism, is that even as it provides a much better ground for genuine, radical monotheism, its adherents were—and are—also capable of continuing in seemingly polytheistic religious practice. We see this as a historical and empirical fact not only in the Neoplatonist and Hermetic religious practices of the eastern Mediterranean, but also in the reality of Hindu philosophy and spirituality past and present—most Hindus recognize a vast array of divine entities, yet every Hindu text I’ve ever encountered insists that there is only one unified ground of reality—Brahman. The various deities of the Hindu pantheon(s)—whether the “high gods” such as Vishnu or Shiva, or the much-less significant local deities of a given village—are understood only as avatars and expressions of Brahman. Whatever divinity they have, they receive from the unity behind, beneath, before, and beyond all things. It’s not for no reason that many translators of Hindu texts into English will end up using the word “God” to refer to Brahman, but not any of the various divinities of the pantheon.

The various deities of these polytheistic systems—whether Greek, Egyptian, or Indic—simply do not “compete” with the One, with God, with Brahman. There is no need, in these religious systems, to exclude those various deities from religious life, because they are themselves just beings that receive their existence from the Holy One. God—a truly monotheistic God—is no more threatened by Zeus or Indra than the strong force of quantum mechanics is threatened by the energy of a train moving over a track. The two realities are of completely different categories, and indeed, the latter depends on the former for its very being; it is constituted by it. (It should go without saying, of course, that one could embrace inclusive/qualitative monotheism while also not believing in any kind of “lesser deity”—and indeed, this is precisely what Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Neoplatonists have done and still do.)

Thus, Numenius’s “inclusive” monotheism is inclusive in this spiritual and liturgical sense as well—we have here a monotheism that can be served by polytheistic religious practices. Again, for those formed in the Abrahamic tradition(s)—such as me!—this will seem stupendous, strange, even foolish. But I hope that, once we have traced the philosophy behind this view, we will see there is nothing inconsistent about this alloy of monotheism and polytheism (even if linguistically it remains confusing!)

But, as I’ve already suggested, this inclusive/qualitative monotheism is of immense value and importance, even for those of us living in the Abrahamic traditions today.10 This is true not only logically, but historically. I hope that my defense of this monotheism above already highlights why any serious monotheist will need to embrace this inclusive/qualitative approach over the exclusive/quantitative one: the latter mode of monotheism results in believing in a deity that can’t explain anything. It’s important to note, for example, that exclusive/quantitative monotheism is vulnerable to the critiques of say, Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion whereas inclusive/qualitative monotheism is not.11 All the genuinely worthwhile refutations of Dawkins’ position operate from the inclusive/qualitative, degrees of divinity, reality-as-participation-in-God position. But Dawkins’ critiques are much more lethal to the exclusive/quantitative monotheistic position.

But even more to the point, though it may indeed be the case that Abrahamic monotheism began with the exclusive/quantitative position, in time, all three major Abrahamic traditions came to embrace the inclusive/qualitative monotheism of Greek philosophy, to various extents and for various periods of time. This is most obvious in what I would consider the “golden age” of Christian theology—extending from Gregory of Nyssa, at the latest, through figures like Pseudo-Dionysius and Maximus the Confessor, and concluding (in the west, at least), with John Eriugena. Each of these thinkers is regarded as a Neoplatonist Christian. The impact of the Neopythagorean, Middle Platonist, and then Neoplatonist inclusive/qualitative philosophical monotheism is massive on this line of thought, and this line of thought is essential to understanding the core of good Christian philosophical theology (indeed, I don’t see how one could make sense of the Trinity from an exclusive/quantitative monotheistic position).12

That said, it is certainly true that there have been lineages of thought in Abrahamic religion that have explicitly rejected this Neoplatonist influence. I have a long series where I explore the impact of voluntarism and nominalism on modern political, social, and psychological thought, but of course both of those doctrines began as rejections of medieval realist Christian philosophical theology—itself the heir of Neoplatonism. Indeed, I think it’s fair to say that most versions of Protestant theology are characterized, in part, by a return to an exclusive/quantitative monotheism. Although many Protestants likely see this as a good thing, a purification of Christianity from various pagan infiltrations, I—along with many Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox13—see this shift as a profound tragedy, a great crisis in western Christian thought. It is, perhaps, no accident that the rise of modern atheism was presaged by this return to a mode of monotheism that is both intellectually and spiritually bankrupt.14

But now I am wondering far afield, and getting a bit polemic as well—even though there is so much more to say on this topic (in particular, and contra Kenney’s own position, I think inclusive/qualitative monotheism has obvious parallels with idealist and monist thought. Indeed, I wonder if we might want to think about “theo-monism” as a way of thinking about inclusive monotheism from a different angle. I hope to address this in the future). So this is probably a good time to conclude. I hope that I have shown how important it is to distinguish these two different lineages of monotheistic thought, not only in order to understand the history of philosophy, but, much more importantly, so that we might recover a genuine monotheistic spirituality for ourselves. As I hope I have shown above, the good news is that genuine monotheism is about recognizing the inherent holiness of all things, of all people, and, at least to an extent, even of all religions.15 The One who creates and sustains us is absolute love for all things, full stop. Our salvation comes not by driving out the heathen, but by recognizing that, already, they—and we—are one in God.

Although I do think Kenney’s approach to monism is a bit stereotyped (this error only comes at the very end of the text and barely impacts its value).

In particular: on pages xxiv-xxvi, 73, & 91.

Of course, in many cases, Greek-speakers identified foreign gods as basically different names for, or versions of, gods they already knew. Even so, the overall size of the pantheon was increasing.

Aten, an Egyptian divinity associated with the solar disc, was, for a short period, the sole deity officially worshipped in Egypt. This short period of semi-monotheism was extinguished soon after the pharaoh who had initiated it died: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atenism

This seems to be the way that this distinction is made in New Testament Greek, for example, with “theos” referring to a god, and “ho theos”—the god—referring to the High God, the Holy One.

This interest in unity was not completely novel, of course. The so-called pre-Socratic philosophers were also interested, though their approach tended to be much less sophisticated, beginning with a naive materialism that greatly limited their metaphysical sophistication.

It does seem that some philosophers after Plato wanted to assume the forms were metaphysical primal, that they just were, without any further explanation. But since the forms were themselves plural, there needed to be at least some ground of their unity, and so this effort to simply assert the forms as primal did not succeed—though it was drawn into a more sophisticated metaphysics in the work of Plotinus.

Parmenides, 137C-142A is a particularly important source for later Middle Platonic reflection on these issues. For a good discussion of this passage, see Deirdre Carabine’s The Unknown God, 23.

All contingent beings require a cause; only the absolute is causeless or “self-causing”. But an entity within contingent reality, that depends on contingent reality for its own existence, cannot be absolute.

I might add here—as Kenney also makes clear—that this distinction between views of monotheism could likely have a big impact on analytic philosophy of religion and analytic theology, as both often seem to assume something much closer to exclusive monotheism in their work, despite its major philosophical shortcomings.

I plan to write more on this particular claim in the future.

One can easily trace the importance of Neoplatonism in Jewish and Islamic thought as well, though I have focused here on Christianity as that’s why I’m most familiar with. Philo of Alexandria, a Jewish philosopher in the Middle Platonist school, is especially important for this Abrahamic/Platonist engagement, for all three faiths.

And, I would imagine, many/most/all Oriental Orthodox and “Nestorian” Christians as well.

I want to clarify that this negative assessment of exclusive/quantitative monotheism is mine, and not necessarily reflective of Kenney’s position.

Of course, I would certainly agree that some religions get us closer to the truth than others. Even so, the list of religions that propound the profound truth of God will, I think, be longer than one entry.

Thank you for writing this, it puts precise words and gives a thorough historical background on a distinction I've long groped towards. I discovered spirituality through the Indian traditions, and despite their centuries of philosophical disagreements among each other, there is always a feeling that at a qualitatively level, everyone knows that they are "talking about the same thing", though through different angles and with different conceptual commitments. Coming from that background, I always found it oddly jarring how strongly the Abrahamic traditions tend to hold to quantitative or exclusivist views. "Everyone's gods are wrong except for mine" doesn't sound like a very appealing view; it fails the basic test of looking the other in the eye and meeting our sameness and depth as human beings. To indulge in a bit of polemic, we could probably draw a direct line from theological excusivism, to the authoritarian tendencies that various branches of Christianity and Islam have often fallen into. An inclusive approach, on the other hand, opens a wide space for dialogue, yet still allows for respect for each tradition's specificities, without obliterating them into a forced kind of unity (as it sometimes happens with perennialist accounts).

Of course, lots of details remain to be clarified, and there is plenty of room for genuine differences in approach. On the crucial question of how unity and multiplicity relate to each other, I'm more attracted to the recognition that there is something inescapably paradoxical there, rather than the kind of foundational layer-by-layer picture that you sketch.

“Most versions of Protestant theology are characterized, in part, by a return to an exclusive/quantitative monotheism.” Indeed! The foundational (and oft-forgotten) treasure of Eastern Orthodoxy is its understanding that salvation is theosis, not simply an Incarnation-based model of salvation. Yet Orthodoxy is also in danger of losing this inclusive/qualitative understanding of God, man, and the cosmos, especially with its influx of Protestant converts (and their exclusive/quantitative theological baggage).

Exclusive/quantitative monotheism is inherently dualistic and seeks, above all else it seems, to maintain an infinite ontological separation between God and man (and All That Is). However, I have also had conversations with those (DBH included, most recently) who seem to espouse a more inclusive/qualitative monotheism but yet still claim that participation in God is somehow not truly, ontological union with the God in Whom we live and move and have our being.

It’s quite obvious to me that inclusive/qualitative monotheism is still in great need of theological explication if we’re to truly distinguish it from incoherent, exclusive/quantitative monotheistic delusion.