Samsara and the Church, Part 1: The Moral Logic of Reincarnation

Pulling on the Threads of Universalism

David Bentley Hart is well known for his syncretistic attitude towards religion, spirituality, and philosophy: though a member of the Eastern Orthodox Communion, he has deep interests in a wide array of spiritual and philosophical traditions, especially the Vedanta traditions of Indian Hindu thought. He uses the basic Vedanta rubric of “being, consciousness, and bliss” when discussing God in his The Experience of God; and indeed, even Hart’s own beloved dog Roland (of blessed memory) assumes Hart is a straight-up Hindu in the book they co-authored (wink, wink) together, Roland in Moonlight.

So it came as a surprise a few months ago when I read “Time After Time” on Hart’s Substack, in which he basically dismisses the idea of reincarnation (“metempsychosis”, the doctrine of rebirth, or whatever else you may want to call it) as uninteresting and unpromising. Today, I’d like to explain why, pace Hart, I think reincarnation, of some form or another, makes sense for Christians—at least for those Christians (such as myself and Dr. Hart) who believe in universal salvation: that all conscious beings will achieve the bliss of union with God.

This faith in the salvation of all is, of course, a minority view in the history of Christian thought, but it is neither novel nor without scriptural and philosophical support. I want to focus this piece on reincarnation, not on a defense of universalism, so if the idea of universal salvation is new to you, or if you think it’s incompatible with Christian doctrine, I would recommend you read Hart’s own That All Shall Be Saved, check out David Armstrong’s defense of universalism, or simply peruse the excellent Eclectic Orthodoxy Blog run by the Rev. Aidan Kimel.

(Moving forward, I will be assuming, gracious reader, that you either agree with the idea of Christian universalism or at least are willing to assume its truth in the argument below.)

The Problem with Christian Universalism

Now if it’s true that all will be saved, Christianity has a problem, or at least some pressing questions to answer. After all, the logic of “infernalism” (the idea that some are saved but others are damned eternally—that is to say, the majority received tradition in the church) is that condemnation to Hell is a just punishment for sin. Does universalism thereby necessarily imply that there are no consequences for sin?

Let’s just ago ahead and test our position on the most extreme, but also most obvious, example: Doesn’t universalism require that Hitler gets to go to heaven? Who would want to be in heaven if it meant hanging out with a genocidal maniac? Are we to believe that someone with Hitler’s beliefs is actually capable, at the time of death, of union and communion with God? Surely someone so dominated by hatred and selfishness is, morally speaking, rather distant from God. Furthermore, if it’s the case that even the worst of the worst get into heaven automatically at death, doesn’t that mean that we can do anything we want here and now without any concern for afterlife consequences? That would seem to encourage a lot of people to make the world a worse place, since they would still get a great afterlife no matter how many innocents they abused in the here and now.

So here are the horns of the Christian universalist dilemma—on the one hand, we don’t believe that even Hitler will be condemned to Hell forever. But on the other hand, we don’t want to hang out with Hitler in heaven; we don’t think Hitler was, in his human state in 1945, actually capable of communion with God; and we think that there must be some real consequence for immoral actions we undertake in our human lives.

Now, Christian universalism does have a decent response to these concerns. I would say that good universalists do not deny the existence of Hell—we simply deny that anyone is in Hell eternally.1 This temporal dimension of the issue is critical. The idea that someone like Hitler might face a Hell-state at death strikes most people, I think, as reasonable and perhaps even morally necessary. And most (serious) universalists agree. So long as the experience of Hell is not eternal, even those condemned at death will still ultimately be saved—hence, one can “believe in Hell” and yet still be a universalist.

Now, it’s important to see that this change in the temporal dimension of Hell does also require, or at least imply, another change too: while most infernalists seem to believe that the purpose of damnation is to punish sinners, the universalist instead sees Hell as a purgative or restorative event or process. That is: to the extent that we are weighed down by sin, that we are not yet capable of union with God at death, Hell is simply the process of being morally and spirituality purified or cleaned so that we can enter into the gracious presence of the Eternal, Infinite, Absolute God.

The word of the Lord came to me: Mortal, the house of Israel has become dross to me; all of them, silver, bronze, tin, iron, and lead. In the smelter they have become dross. Therefore thus says the Lord God: Because you have all become dross, I will gather you into the midst of Jerusalem. As one gathers silver, bronze, iron, lead, and tin into a smelter, to blow the fire upon them in order to melt them; so I will gather you in my anger and in my wrath, and I will put you in and melt you. I will gather you and blow upon you with the fire of my wrath, and you shall be melted within it. As silver is melted in a smelter, so you shall be melted in it; and you shall know that I the Lord have poured out my wrath upon you. (Ezekiel 22:17-22)

This is a significant difference. While the classic (or at least received) view of Hell sees the deity as actively, perhaps even sadistically, enjoying the punishment of sinners in Hell, the universalist view of Hell instead casts it as a painful but necessary stage in moving towards the bliss of theosis (divinization; union with God). Indeed, it might be best understood through a medical metaphor: if you have broken your leg, the doctor will have to reset the bone before applying the cast; otherwise, the leg may heal crooked. Resetting a broken bone, I am told, is an extremely painful process. But it is necessary for true and full healing to occur. Hell, on the universalist view, is a similar process: painful, but necessary for proper healing.

As long as we are on earth, the love that unites us will bring us suffering by our very contact with one another, because this love is the resetting of a body of broken bones. Even saints cannot live with saints on this earth without some anguish. There are two things which [people] can do about the pain of disunion with other [people]. They can love or they can hate. Hatred recoils from the sacrifice and the sorrow that are the price of this resetting of bones. It refuses the pain of reunion. (Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation, p.72)

Now, this understanding of Hell, I think, addresses all three of the concerns we raised above about universalism, at least to a degree: 1) no one will have to hang out with Hitler in heaven—at least not Hitler in the psychological, spiritual, and moral state he existed as in 1945. 2) we can readily agree that Hitler will need to undergo substantial purification, rectification, and healing in order to be capable of union with God. 3) Hitler will indeed reap what he sowed; his horribly immoral actions on earth will result in real—though not eternal—suffering after his death.

Now, the perceptive reader may see that what the universalist does with Hell is essentially transform it into Purgatory—Hell here is an intermediate state in which our sin is “burnt off” so that we can enter into the Paradise of God’s presence. Now, many of us universalists would argue that the common, received understanding of Hell was itself a transformation of an idea that was originally more like Purgatory in the first place, and so we would see our “Purgatorification” of Hell as the fixing of an old error.2 Even so, I think this characterization of the universalist view of Hell is accurate, even if a bit oversimplified.

Even so, if we think through the details of the universalist vision of Hell, we might still have questions and concerns. If we are imagining the received traditional view of Hell—forlorn souls trapped in a fiery pit—we may wonder how this experience is supposed to purify, much less heal anyone. If we took a human being and tortured them for decades in a fiery pit, I don’t think anyone of us would assume they would exit that process psychologically, spiritually, or morally healthier than they were when they entered it. Indeed, we’d likely assume the opposite.

So, then, how is Hell supposed to actually help the wayward sinner be joined to God? It would seem that what is required is not simply pain or punishment, but some process that can spiritually transform the human soul. Well, the Christian universalist here might argue that Hell is not a fiery pit, but something more like a remedial classroom: perhaps at death, those of us still burdened by sin will undergo a process of further spiritual education—which still of course might involve real suffering, but also plenty else besides. Interestingly, both the “pit” and the “classroom” models of Purgatory/Hell imply that we will have some kind of body—that is to say, a mind-body complex, something along the lines of Paul’s soma psychikon—through which we can sense, experience, and think, since a soul bare of a body probably lacks the faculties to do so, and therefore probably can’t learn anything.3 And perhaps we assume that this Purgatory-body is basically identical to the body we have here and now. This would accord with the Christian tradition of understanding resurrection as the resuscitation of our earthly body, even if in some transformed mode. With this body, perhaps, we can do the work necessary to be transformed from our sinful state to one ready for theosis.

While I certainly think that this view of Purgatory-Hell is more suitable, both logically and morally, than the fiery pit, it still leaves a lot of unanswered questions. Is the mind-body in Purgatory-Hell subject to the illnesses, physical and mental, that we bear in this world? If so, couldn’t that prevent someone from ever “succeeding” in Purgatory? Can a sociopath ever learn to not be sociopathic? Can someone with a severe learning disability, who is nonverbal and unable to even care for their body, successfully navigate the challenges of this Purgatorial assignment?

It would seem that having a rather different body in this Purgatorial chamber would be of great help, at least to those people whose current mind-bodies are severely compromised (and this category may in fact include the vast majority of us). While we could try to argue that perhaps our Purgatory-body is basically like the body we have now, except that it doesn’t have any of the problems that held us back in this world, that strikes me as both special pleading and would also seem to make the purgatorial process itself unnecessary—if we are gifted with a completely healed mind-body at the outset, might that mean we would already be suitable for union with God? In that case, what even needs to be purified or healed? Such a position would bring us back to the original dilemma of Christian universalism we introduced above.

Instead, it seems like the Purgatory-body would need to be appreciably different from the body we have now. The soul or spirit (whatever exactly this is—a topic for another time!) would need to undergo the healing, but would need a new bodily form in order to do so, one not perfected and yet not necessarily subject to some of the limits that held it back in its time on earth. And this of course would mean that the “soul” is separable from any given mind-body, such that the soul could take on a body rather different from the one it happens to be attached to now. And here is where I think the Indic or Dharmic doctrine of reincarnation recommends itself.4

[Edit on 9/13/2025: Nicholas Smith rightly points out in a comment below that there are other options for how to conceive of Hell and even of a Purgatory-Hell apart from the ones mentioned here, including a view common in Eastern Orthodoxy that has much merit. You can view his comment here. As I point out in my response to him, I don’t that view resolves the problems of traditional Christian views on the subject, and I still think that some version of reincarnation is probably preferable, but I should have mentioned and engaged it here.]

Facing Samsara

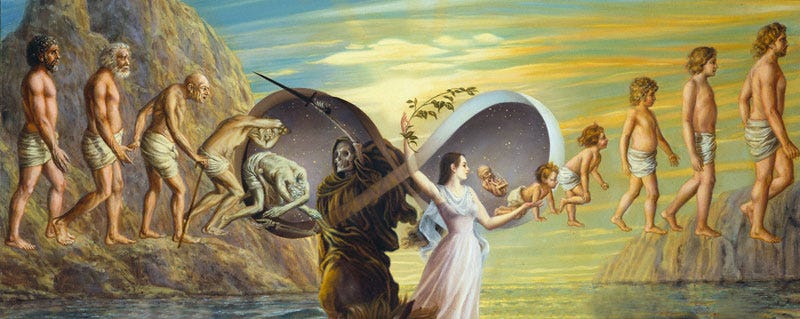

All three of the classic Indic or Dharmic religions—Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism—affirm the idea of Samsara.5 Samsara is the idea that the material world we live in now is an endless process of birth and death which is full of suffering. Crucially, all three religions teach that the center of human consciousness (a “soul”: loosely the atman and/or jiva in Jainism and Hinduism; Buddhism’s engagement with this reality is…more complicated. I’m going to use jiva below for simplicity’s sake) is itself functionally eternal. This jiva is attached, in some way, to a given mind-body complex for its duration. But when that body dies, the jiva is attached to a new body that is being born—that is to say, all three faiths endorse some version of reincarnation, rebirth, or metempsychosis. This process repeats endlessly, until the jiva finds a way to escape Samsara entirely—the act of moksha: liberation. Moksha is the equivalent of complete beatific salvation in the Christian sense; for Hindus in particular, it involves theosis: union, or at least intimate communion, with God.

And indeed escaping Samsara is the goal, according to all three faiths. This is because all three religions are honest about the fact that this life is full of suffering. Of course, it’s not only suffering; there is real joy in life, too. But the basic insight about Samsara, this process of endless being and becoming in the cosmos, is that it’s more suffering than joy, and that because there is always more suffering to come, even the joy is overshadowed by that future suffering, and so it’s a state that the jiva will want to escape.

Now, the details of how one goes about escaping Samsara differ between the three faiths (though there is definitely some crossover, especially in Hinduism, which endorses a “many paths” philosophy on the matter), but that the goal is to get out of Dodge is undisputed.

So, a given jiva finds itself caught in the constant churn of Samsara, suffering much through a seemingly endless process of birth, death, and birth again. Now, the specific metaphysics of how this process of reincarnation, rebirth, or metempsychosis occurs differ not only between the three religions but between schools within them. The “mainline” versions of Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism all teach that, in addition to the earthly realm we live in, there are also heavenly and hellish realms that a jiva can be born into. Importantly, though, neither these heavens nor hells are states that a jiva can live in indefinitely. Once the merit or demerit (often referred to by transliteration in English as karma, although this Sanskrit word is complicated and has many various meanings) of past lives has been exhausted, one dies in the heavenly or hellish realm and will be reborn again, generally speaking in the material realm we know. But, all three faiths also teach, eventually, every jiva can and will achieve liberation from Samsara—with no future rebirths in any realm whatsoever. It may take some jivas many, many, many lifetimes to achieve this, but the assumption is that eventually, everyone will.6

In other words, the Indic/Dharmic faiths are universalist when it comes to salvation. Yet, we also see that they do not deny that there can be and indeed is a Hell-state after death—both literally believing in a hellish reality that a jiva who has done horrible things will descend to, but also that our future lives even on earth can be, in a sense, quite hellish. In either case, though, no jiva lives in any Hell-state eternally. And for all three faiths, the sufferings of either Hell or our own realm should ultimately function as a lesson, calling us to wake up to the reality of suffering, and therefore seek a path to liberation from Samsara—suffering is not really a punishment, but is just the consequence of immoral action. Once we realize that, we can change our ways, and change our future.

Now, obviously, there are many differences between the Dharmic and Christian views of the soul, of afterlife, and of Hell. But it seems to me that the Dharmic view of reincarnation works very well to explain how a Christian universalist can both affirm the reality of a Hell-state but also believe that, in the end, everyone is saved. What the idea of Samsara gives us is a clear picture of how souls both suffer consequences for immorality and yet also are continually given the opportunity and means to be liberated from suffering.

What’s interesting is that, even if we removed the literal Hells of traditional Jain, Buddhist, and Hindu teaching, the Samsara of our own world would itself function well as a kind of Purgatory-Hell: to the extent that we do not achieve liberation from Samsara (in Christian terms, union with God through Christ) in a given lifetime, well, we will enter a new life and try again. And we’ll try again and again until we get it right. Hell, on this view, would be the endless process of birth and death, with all its attendant suffering, that we face here and now.

Put another way, the basic Dharmic view is that, in a real way, we are living in a universalist Hell right now. This is both bad news (obviously) but also good news. It’s bad, of course, because it means facing the simple fact that to live as an embodied being in this universe is to know suffering and to be constantly and inescapably subject to suffering. And the Dharmic religions teach that we will keep undergoing suffering unless and until we seek liberation from this seemingly endless process of birth, death, and rebirth. To the extent that we don’t seek this liberation, we basically can be here for an infinitely long (though not properly eternal) duration of time.

But the good news that all three Dharmic faiths teach is that we can choose to seek liberation, and to the extent that we are honest in doing so, all three religions teach that we will achieve our goal—though, admittedly, probably not in our current incarnation.

But what I think is important to see is that this view of Samsara and rebirth gives us the exact framework that the Christian universalist wants and needs: there is a real Hell-state in which we suffer the consequences of our past immorality, but while that Hell-state may itself be eternal, no individual soul need suffer it eternally. In other words: there is a Hell, we live in it, but we can leave.

It seems to me that this addresses all the horns of our dilemma above quite gracefully, giving a much clearer picture of how the Hell-state (here and now) can actually be purgative. For while we said above that the classic/received picture of Hell as a fiery torment seemed a bad candidate for a truly purgative/healing process, I think we can agree that human life on this earth is, most of the time, different: there is real suffering, to be sure, but also real opportunities to learn, to grow, to deepen one’s consciousness of God and thereby actually be transformed, to begin to undergo genuine theosis.

So, that’s my view on the matter: we Christian universalists should probably endorse at least some version of reincarnation, and if we are going to do so, it would likely behoove us to pay attention to the religions that have taught this for millennia—not because we need to copy every aspect of their doctrine, but because, just as the Church learned much from pagan Greek philosophy (shoutout to Plato, Plotinus, and many others), we can also learn much from Dharmic philosophy too.7 (I also drew on Dharmic (specifically, Hindu) philosophical theology last week in my discussion of different approaches to monotheism, so if this “theology of religions” approach interests you, you may want to read that piece as well.)

Meanwhile, if you have an alternate proposal for a Christian universalist understanding of Purgatory/Hell that does not involve reincarnation, I’d love to hear it! Please feel free to comment below.

I’ll conclude this piece here, but there is of course much to say. In the next two weeks, I plan to continue this series by threading the more general reasoning presented here with more specifically and particularly Christian reasoning: first, by exploring how C.S. Lewis’s The Great Divorce can be read through a Dharmic-reincarnation lens, and second, by exploring how scriptural statements on resurrection can be read in that same lens as well.

I should note that there are some number of preachers and theologians who do seem to deny Hell flatly, though I am not sure how prevalent this view is. To the extent that anyone holds such a view of universalism, I disagree with them.

For more on reading the passages about Hell in scripture through a universalist lens, I recommend Hart’s That All Shall Be Saved as well as his introduction to and notes within his translation of the New Testament.

I am assuming here that the some pnuematikon of genuine resurrection is a state only of the fully healed and blessed.

This view of the soul may involve a change in metaphysical views of the soul and the person; for example, the Thomistic vision of the soul as inherently tied to (a given) body might either need to be replaced or modified. Likewise, those Christian thinkers who would prefer to understand human embodiment without a soul at all would need to modify their position (substantially!) to work with the Dharmic view I outline below. In general, the approach I present here would require some form of idealist or theo-monist position. I have outlined elsewhere why I think some version of this metaphysics is probably required anyway, so I don’t see this as a problem—though I recognize others might.

I believe that Sikhism, which also sprang from the Indic/Dharmic tree, though much later, also affirms Samsara—but I am woefully ignorant of the details of Sikhism.

It’s worth pointing out that there do seem to be at least some schools within Hinduism that are not strictly speaking universalist—such as the Dvaita school formed by Madhvacharya. But this is a minority position within the Dharmic faiths.

There is precious little engagement of reincarnation by Christian thinkers. Origen, famously, seems to have explored the idea, though scholars debate precisely how to parse his short statements on the subject. I imagine there has been more discussion of the subject in the past century or so, but, as I hope this piece makes clear, I think we need a lot more discussion of the subject!

I've read David in a few places showing openness to gilgul in the circumstances here described, as a final resort in the purgation of the particularly wicked, so I wouldn't say it's totally pace his perspective--I don't know that apart from "Time After Time" he's written on it in a sustained way, and in that article, I think what he's tackling is mainly a kind of modern pop-reincarnation that was hot in the New Age movement. Otherwise, though, I think you're spot on that universalism requires some kind of metempsychosis--as early as Philo of Alexandria.

Thank you for this provocative but well thought out article, Scott! I have some hesitation though in accepting this doctrine as truly the best way of thinking of Universalism. Part of this has to do with the way you frame the problem of Universalism without Reincarnation, I think leaves out the most convincing view on Universalism I have heard spoken of which is especially drawn from St. Isaac the Syrian, but broadly considered valid for infernalists and universalists in the Orthodox Church. This involves a sort of understanding that those who instead of seeking out Godin this life and virtue and love, hand themselves over to passions that lead one astray from their proper end--e.g. virtue and piety. Moreover, they become attached to ideas like Melkor--if you've ever read the Silmarrion--of bringing into being something outside of Being based on their own or demonic phantasms as to deify themselves apart from God. If this is the case, after death when all illusions are removed and one is deprived not only of what they cared about in this life, but made to realize that all that truly is, is God and his self-giving love, they will in turn experience great pain--hell--and thus they don't as much just undergo education or purgatory, but realistically, suffer until Love wins out over their finite attachment to what is no longer accessible to them and caring about what they now see is illusion or at least not available to them and thus Hitler would suffer the agony of his ego not being worth anything, all he cared about in life as taken away from him, and love which burns for it is at odds with his nearly incomparable commitment to self deification and anger and all manner of the passions. I find this understanding of universalism quite compelling.

Secondly, and I think the more difficult challenge of accepting reincarnation is it seems to not be detachable from Karma and this is where Plato for instance says a bad man will come back as a woman--obviously a worse condition at the time lol--and unto lesser and lesser forms of life considering their actions. This thus can involve human beings no longer being even human.

But even his idea is much better than what we find in the Hindu tradition and it's adoption of Karma because it is used to justify to this day the class system in India which is so prevalent even among the Christians there in the Malankara Orthodox Church where Brahmins usually can't see it as a possibility of marrying even a lower class. And more broadly it is used--logically I think--to say, the situation one is born into, their class, their value, their privileges are merely the product of Karma for how they lived in their last life.

Now you might argue that reincarnation does not necessarily need to involve such social inqequality or injustice or a human being becoming an animal, but the logic behind reincarnation--that one's current birthplace and body, etc... is the product of one's past life is quite hard to separate from reincarnation. This is why I think it is better to focus on particularly considering the vision of hell I present above, or further alternatives instead of turning toward reincarnation for an answer.

Nevertheless, I understand why you would be drawn to such an idea as it is difficult to come to a complete understanding how one is to go from mass-murderer to ever greater union with and participation in God as to become like or God to the degree such a thing is possible. But I think it's worth pursuing this question along more traditional lines for the reasons outlined above. Ultimately, too it is hard to really know anything for certain at all for what comes after this life. As Maximus the confessor says, the world is like a womb, and as Gregory of Nyssa says, we will be but like newborn babes opening their eyes for the first time when encountering the next life and God, etc...